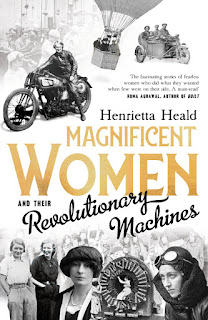

Today I am delighted to feature Henrietta Heald's Magnificent Women and their Revolutionary Machines. This is the lost story of Britain's trailblazing, boundary- breaking women engineers. To whet your appetite, I have an extract for you and also the chance to win a print copy (UK only). Details on how to enter the giveaway are at the foot of this post.

Today I am delighted to feature Henrietta Heald's Magnificent Women and their Revolutionary Machines. This is the lost story of Britain's trailblazing, boundary- breaking women engineers. To whet your appetite, I have an extract for you and also the chance to win a print copy (UK only). Details on how to enter the giveaway are at the foot of this post.

‘Women have won their political independence. Now is the

time for them to achieve their economic freedom too.’

This was the great rallying cry of the pioneers who, in

1919, created the Women’s Engineering Society. Spearheaded by Katharine and

Rachel Parsons, a powerful mother and daughter duo, and Caroline Haslett, whose

mission was to liberate women from domestic drudgery, it was the world’s first

professional organisation dedicated to the campaign for women’s rights.

Magnificent Women and their Revolutionary Machines tells the

stories of the women at the heart of this group – from their success in fanning

the flames of a social revolution to their significant achievements in

engineering and technology. It centres on the parallel but contrasting lives of

the two main protagonists, Rachel Parsons and Caroline Haslett – one born to

privilege and riches whose life ended in dramatic tragedy; the other who rose

from humble roots to become the leading professional woman of her age and

mistress of the thrilling new power of the twentieth century: electricity.

In this fascinating book, acclaimed biographer Henrietta

Heald also illuminates the era in which the society was founded. From the

moment when women in Britain were allowed to vote for the first time, and to

stand for Parliament, she charts the changing attitudes to women’s rights both

in society and in the workplace.

Extract

2. A Brilliant

Inheritance

The Parsons family’s immersion in engineering and invention

had its roots in an ancient settlement in the geographical centre of

Ireland. So closely was Parsons history

woven into Birr and its romantic medieval castle that, by 1885, when Rachel was

born, the place had been known for 365 years as Parsonstown. Its name came from

the activities and influences of two Parsons brothers who had migrated from

East Anglia to Ireland in late Tudor times, acquiring land and titles, which

they passed on to generations of descendants. From this inheritance would

eventually derive the earldom of Rosse.

Parsonstown’s prominent status in King’s County (now County

Offaly) indicated a longstanding allegiance to the English Crown, but Rachel’s

great-grandfather Laurence, a politician, had broken with tradition by his

trenchant opposition to the proposed union between Great Britain and Ireland.

Described by the Irish republican leader Wolfe Tone as ‘one of the very, very few

honest men in the Irish House of Commons’, Laurence, who favoured complete

independence for Ireland, had resigned from politics in protest when the Acts

of Union became law in 1800. That year also saw the birth of his son William,

the future engineer and astronomer who would one day bring worldwide fame to

the name of Parsons.

By the time William Parsons inherited Birr and the earldom

of Rosse from his father in 1841, he was already well on the way to

transforming human understanding of the stars. Two years earlier, Thomas Romney

Robinson, the director of the Armagh Observatory, had visited Birr to inspect

an extraordinary telescope

that had been erected in the castle grounds. Called a

Newtonian reflector, and based on a design by John Herschel, the instrument

included a three-foot-diameter speculum, or mirror, and had been built to

observe objects farther out into space and more clearly than had ever been

possible before.

Robinson stayed at Birr for more than a week, trying out the

new telescope with the help of another prominent astronomer, the Englishman

James South. The two men were amazed by what they saw. Star clusters, nebulae,

double stars – all stood out magnificently, and a host of new objects were

identified on the surface of the moon. ‘It is scarcely possible to preserve the

necessary sobriety of language in speaking of the moon’s appearance with this

instrument,’ wrote Robinson. Indeed, the Earl of Rosse would later draw on

these observations in his contribution to the development of lunar mapping.

But, as far as the noble inventor was concerned, the three-footer was only the

start. He had already conceived of the idea to build at Birr a telescope far

surpassing any of its predecessors – an instrument with a six-foot-diameter

speculum that would acquire notoriety as

the Leviathan of Parsonstown.

Construction of the Leviathan, which took almost two years

and entailed many setbacks, was an astonishing feat. Casting the speculum

required a huge foundry – created in the dry moat surrounding the castle – in

which peat-fired furnaces were used to heat three iron crucibles, each twenty-four inches in

diameter and containing 1.5 tons of a tin and copper alloy. The molten metal

was transferred by means of cranes into an enormous mould, where it was

carefully cooled over a period of sixteen weeks.

Thomas Romney Robinson was present on one occasion when the

crucibles were lowered into the furnaces. ‘The sublime beauty can never be

forgotten by those who were present,’ he wrote. ‘Above, the sky, crowded with

stars and illuminated by a most brilliant moon, seemed to look down

auspiciously on the work. Below, the furnaces poured out huge columns of nearly

monochromatic yellow flame, and the ignited crucibles during their passage

through the air were fountains of red light.’

The next stage was the laborious and time-consuming process

of grinding and polishing. ‘The speculum was successfully cast, but the surface

was covered with minute fissures, about the breadth of a horse hair,’ explained

William Rosse later in a paper to the Royal Society. ‘These we resolved to

grind out.’ The grinding continued for nearly two months, the machinery working

for part of the time at night. The speculum was then polished, and its

performance equalled expectations.

The telescope’s fifty-six-foot-long wooden tube and hoist

were fixed between two castellated brick walls fifty feet high and seventy feet

long. Movement of the tube was controlled by chains, pulleys and

counterweights. A platform for observing objects at low altitude was built at

the southern end of the walls. For high altitudes, a long gallery mounted on

the west wall moved across the central space to follow the tube’s lateral

motion. At least three assistants were needed to help the observer by moving

the winch and shifting the galley.

It had long been recognised by astronomers that the larger a

telescope’s mirror, the more light could be ‘grasped’, or collected, allowing

fainter and more distant objects to be studied – and what made the Leviathan so

powerful was its tremendous light-grasp. At the time of its creation in the

1840s, it was by far the most sub- stantial telescope ever built, and it would

remain the largest telescope in the world for almost three-quarters of a

century, until it was over- taken in 1917 by the one-hundred-inch Hooker

telescope on Mount Wilson in California.

About the Author

Henrietta Heald is the author of William Armstrong, Magician

of the North which was shortlisted for the H. W. Fisher Best First Biography

Prize and the Portico Prize for non-fiction.

She was chief editor of Chronicle of Britain and Ireland and

Reader’s Digest Illustrated Guide to Britain’s Coast. Her other books include

Coastal Living, La Vie est Belle, and a National Trust guide to Cragside,

Northumberland.

You can follow Henrietta here: Twitter | Website

Thanks to the author for a place on the tour.

Check out these other great bloggers

Giveaway ( UK only)

To win a print copy of Magnificent Women and their Revolutionary Machines, just Follow and Retweet the pinned Tweet at @bookslifethings.

Closing Date October 1st 2019

and there is one winner.

*Terms and Conditions –UK entries only. The winner will be selected at

random via Tweetdraw from all valid entries and will be notified by Twitter

and/or email. If no response is received within 7 days then I reserve the right

to select an alternative winner. Open to all entrants aged 18 or over. Any personal data given as part of the

competition entry is used for this purpose only and will not be shared with

third parties, with the exception of the winners’ information. This will passed

to the giveaway organiser and used only for fulfilment of the prize. I am not

responsible for despatch or delivery of the prize.

Oh what a great book, as a woman who became a scientist when "women didn't", the daughter of a woman who became a scientist when "women REALLY didn't", mother to a daughter who became an engineer and grandmother to a 10 year old who wants to become an engineer, I'd love to read more about the women who fought to lay the groundwork for four generations of my family to be able to follow our passions. Have retweeted @janesgrapevine

ReplyDeleteI wish you luck in the giveaway, it certainly sounds right up your street! Thanks for stopping by and reading.

DeleteThanks for the blog tour support Pam x

ReplyDelete