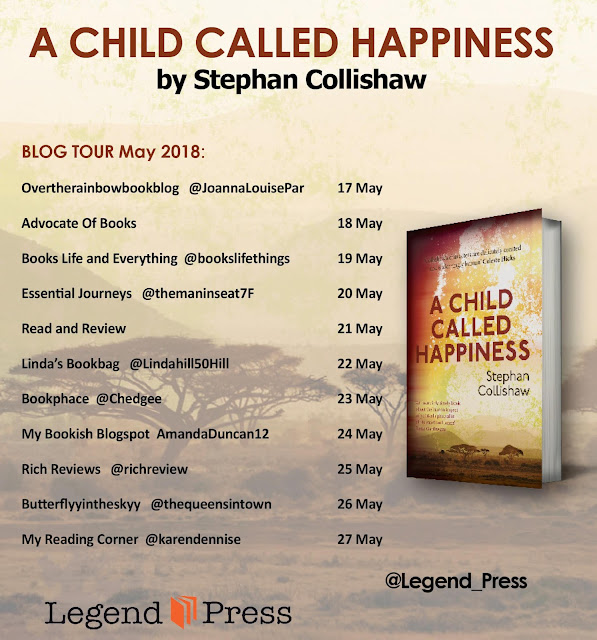

It's a privilege to be welcoming Stephen Collishaw to Books, Life and Everything to talk about his writing life and his book, A Child Called Happiness which was published by Legend Press on 17th May 2018. Stephan has agreed to answer some of my questions but before he does, here's a little about the book to whet your appetite.

Three days after arriving in Zimbabwe, Natalie discovers an

abandoned newborn baby on a hill near her uncle’s farm. 115 years earlier, the

hill was home to the Mazowe village where Chief Tafara governed at a time of

great unrest. Faced with taxation, abductions and loss of their land at the

hands of the white settlers, Tafara joined forces with the neighbouring

villages in what becomes the first of many uprisings.

A Child Called Happiness

is a story of hope, resilience and reclamation, proving that the choices made

by our ancestors echo for many generations to come.

Welcome Stepan to the blog today. Would you like to start by telling us a little about yourself and how you started as a writer?

I

was brought up on a working-class council estate in Nottingham, one of

four boys in a fairly rough-and-tumble household. I went to the local

comprehensive school and managed to fail all of

my O levels. From an early age, though, I had an interest in books and

reading. While we were at school, my mother went to university and her

books filled the home. Reading had always been important in our house,

we didn’t get a television until I was fourteen.

When I was a teenager I devoured the novels – George Elliot, Jane

Austen, the poetry and letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins (which I was

reading as I failed my O levels), the plays of Christopher Marlowe. At

the same time, at school, I was introduced to the

stories of Guy de Maupassant, which really fired my imagination. I

would play truant from school, but rather than smoking cigarettes and

drinking cheap cider behind the Co-op, I went to the park and wrote

stories. It was when I went to Lithuania, though, in

1995, that I finally found the first story that I needed to write.

Writing became, then, a means of exploring a place, a way of

understanding something of the history of a city. How things came to

happen. My writing was a moral and historical journey of discovery.

That first novel, The Last Girl, published by Sceptre in 2003 was my

love song to the city I had fallen for.

A Child Called Happiness is set in Zimbabwe. Have you ever visited the

country and if so what effect did your visit have on you?

Zimbabwe

was the first foreign country I ever visited. I was twenty and had

never been abroad when the opportunity came up. It was 1989. I remember

the precise moment that the doors to the plane

opened and the hot air hit me and I climbed down the stairs and stepped

foot on a different continent. It was a magical moment. One of the many

magical moments I was to have there. I stayed for just over a month,

travelling around the country. Over the next

couple of years, I went back again a couple of times, spending a few

months out there. The people I met were incredibly generous, opening

their homes to me. I stayed in villages in the country and in small

township houses. There were some beautiful moments.

Staying at a village in the north of the country, I spent the evenings

sitting by a fire, roasting peanuts and learning to sing Shona songs.

Wandering away from the fire, the night sky was a huge expanse of stars,

such as I had never seen before. There were

other moments, too, that were not quite as poetic. Zambia, which I also

visited, was going through a difficult period; it was the last days of

the rule of Kenneth Kaunda and there were bread riots. The roads were

obstructed every few miles by armed road blocks,

where we would be interrogated at gun point. The townships were

unfriendly and there were very visible signs of malnutrition,

particularly in the children. In a small town in the east of the

country, I was arrested. I was taken down to a dirty police station

on the edge of the town with the person I was travelling with, who had

more experience travelling in Africa. After a short while, the police

released my friend and kept me for questioning. As he was leaving, he

bent down and whispered in my ear, ‘If they say

they’re going to shoot you in the morning, don’t worry.’ With that he

left. I was petrified. For a good couple of hours they kept me there,

questioning me. As the sun dropped, I sat outside the back of the police

station under armed guard, as some friends

negotiated my release. It was a salutary experience. At twenty I had

thought I was all grown up. I realised then, that I was not as brave as I

thought. It was an incident that inspired one of the scenes in my new

novel.

What was the inspiration for your book?

I’ve

been wanting to write a novel about Zimbabwe ever since I went there.

Indeed, when I started writing one of my first novels I wrote about the

country. I gave that novel to my elder brother

to read – he’s an artist, and I respect his opinion. He lost the novel.

As a novelist I like to unpick the history of place. I see past events

as being constantly present, a psycho-geography of a city or a country.

Places are never just bricks and mortar,

fields and rivers, we imbue places with feelings, significances.

History is a spirit that haunts the landscapes we live in, and my

writing is in part an exploration of that. The expropriations of farms

in Zimbabwe (and in South Africa) is a painful subject.

I’ve tried to explore that in this novel.

Without giving away the plot, can you tell us a bit about A Child Called Happiness?

A

Child Called Happiness opens with the discovery of a child on a granite

outcrop of rock above the Drew farm in northern Zimbabwe. Natalie, the

young woman who discovers the baby, has gone

to stay with her uncle, the owner of the farm, running from her own

problems back in London. But things are far from peaceful at Drew’s

farm. The authorities are keen to get their hands on the land and a

stand-off with the local War Veterans seems increasingly

inevitable. Meanwhile a second story winds alongside the first. It’s

1894 and Tafara has just taken over the land in the upper Mazowe Valley

from his father, but white incursions into the area are becoming more

regular and tensions are rising. Tafara must

decide how to respond when his cattle are exterminated by the new white

authorities.

Which aspects of your writing do you find easiest and which the most difficult?

I

love researching my novels. My first novel was set in Vilnius, the

second in Afghanistan and my third in northern Poland while this one has

been set in Zimbabwe. Each deal with the history

of the places they are set in. Its not enough to know, though, about

the grand sweep of historical events, it’s also important to try to

understand the small detail of life: what people ate, how they dressed,

what they read, what music they listened to. I

love reading around subjects and looking at photographs, where they’re

available, examining the detail of everyday objects. The difficulty is

ensuring none of that research is at all apparent to the reader. It

should be part of the tapestry of the background

of the writing, a confident, textured backdrop that compliments but

does not distract from the main events. It’s also hard to know when to

stop doing the research. It can be a great distraction, particularly in

the internet age, to ensure that every single

detail is checked. Knowing when to say it’s not important is key to

actually getting a novel written.

You work as a teacher. Do your pupils know that you are a published

author and are you ever tempted to talk to them about your writing?

My

students know that I write, how they react to that is diverse and often

amusing (the assumption that as a published writer I should be rich and

not have to work as a teacher, is pretty universal).

I try to encourage as much writing and reading in school as possible.

The students I work with are not necessarily from backgrounds where

books are common at home, or where reading is part of the culture and

today’s knowledge-heavy curriculum, and the pressure

for ‘results’ often squeezes creativity out of school life – fighting

against that is incredibly important. I like to get other writers in to

school whenever possible, helping students to develop their confidence

in finding their own creative voice. Where

students have gone on to take their writing seriously, publishing and

performing their poetry and stories, it’s been a great source of pride.

Finally do you have you any projects you can share?

I’m

writing another novel now, though it’s developing at an agonisingly

slow pace. Partly that is because I also run a small press which is

wonderful but takes up a huge amount of my time. My

project, Noir Press, aims to bring some of the best writing from the

Baltic states to an English audience. So far, we have published a number

of great novels by some top Lithuanian writers, including the

world-renowned Jewish-Lithuanian writer Grigory Kanovich.

Our new book by the Lithuanian-Ukrainian writer Jaroslavas Melnikas is

just being finalised; we’ll be launching it with the writer at the

Lowdham Books Festival at the end of June and at Ukrainian House in

London on July 1st. Details of this project is at

www.noirpress.co.uk

Thanks you so much, Stephan , for those fascinating answers.

My Thoughts

This is a book which crackles with atmosphere and its descriptive writing captures the feel of Zimbabwe and life in Africa. It melds together the present day story of Natalie's visit to Zimbabwe with that of 1894 when the white incursions were threatening to take over the land from the native inhabitants.

The story explores issues from Zimbabwe's history which were painful to live through. You can feel the heat of the country in this evocative writing and there are some emotional moments which seem to be seared into the landscape. It can be a painful read at times but ultimately rewarding. The author makes it clear that ultimately there are no winners in the situation and both sides feel they have an entitlement. Being displaced from the land which their ancestors farmed and lived in is a feeling which is not easily brushed off. It is imprinted within a person.

In short: Desperation and the heat of Africa fill this atmospheric writing.

About the Author

Stephan Collishaw was brought up

on a Nottingham council estate and failed all of his O-levels. His first novel

The Last Girl (2003) was chosen by the Independent on Sunday as one of its

Novels of the Year. His brother is the renowned artist, Mat Collishaw. Stephan

now works as a teacher in Nottingham, having also lived and worked abroad in

Lithuania and Mallorca.

Thanks to Stephan Collishaw and Imogen Harris of Legend Press for a copy of the book and a palce on the tour.

Check out the rest of the tour!

Comments

Post a Comment